Near the top of an impossibly steep and winding street in the hills of Echo Park, there sits a quietly fading house, its cracked gray shingles and worn brown siding dappled by the shadows of surrounding trees. It was once the home of one of Echo Park’s many notable artists: the groundbreaking printmaker, Paul Landacre, a highly regarded woodcut artist from the 1930s. His art captures the mood of the neighborhood and of California during his era. He lived in his hillside cabin from 1932 until his death in 1963. Born in Columbus, Ohio, he was an athlete as a youth. During his sophomore year at Ohio State University, he contracted a life-threatening illness that left him partially disabled. Landacre moved to California for his health. He eventually settled in Echo Park with his wife, Margaret McCreery. The Landacres’ rustic cabin now overlooks the Glendale Freeway. The Landacres purchased the property on El Moran Street in 1932, when he was just starting to earn renown for his work. L.A. was then one of the fastest-growing cities in the United States — but in Edendale, as it was then known, you could live amid native black walnut trees, possums and scrub jays. Weeds have swallowed up the staircase of the cabin, pictured, and its windows are either broken or boarded up. The big live oaks Landacre etched with such brio are still there, but the old curving street — the Landacres had a whole block to themselves — has been sealed off and is eroding away. This section of the neighborhood once was known as the Semi-tropics Spiritualist tract, and the Landacre home was declared a City of Los Angeles landmark (Historic Cultural Monument No. 839) in March 2006. Landacre’s name is still painted on the mailbox of the now-padlocked home.

The Brits who built Los Angeles

Los Angeles was a backwater with a population of barely 50,000 people when John Parkinson arrived in 1894. He had no formal education, no contacts, and just a few dollars and a tool box to call his own. By the time of his death he had designed many of the city's iconic buildings, including the city's first skyscraper, the first luxury hotel, the Homer Laughlin Building (now home to the Grand Central Market), high-end department store Bullocks Wilshire, the Memorial Coliseum, which hosted the 1932 and 1984 Olympics, and Los Angeles' City Hall. What City Hall may lack in iconic recognizability it makes up for with an almost subconscious symbolic power. Though few Angelenos could draw the building from memory, they have seen it over and over again, and so, at this point, has much of the rest of the world. Every LAPD badge has borne its image since 1940, and the building began playing its series of major roles in television shows like “Dragnet,” “Perry Mason,” and “The Adventures of Superman.” A 1953 adaptation of H.G. Wells' “The War of the Worlds” even blew it up, at least in scale model, setting off a cinematic tradition of felling the large buildings of Los Angeles. Parkinson’s story sounds like the classic American Dream, with a British twist - he was the son of a millworker and born in Scorton, Lancashire. He is virtually unknown in his native land, and all but forgotten in the city he came to call home. Others from the British Isles who left their mark in early Los Angeles history are better remembered - Belfast-born William Mulholland, whose life inspired the movie, Chinatown, oversaw the huge engineering project that controversially brought water to the city in 1913 and was memorialized with Mulholland Drive. And Welshman Griffith J Griffith (not to be confused with American film director D.W. Griffith) gave most of his vast lands to what became the 4,310-acre Griffith Park, which is home to the Griffith Observatory and Greek Theatre, projects he both funded. As for Parkinson's legacy, more than 50 of his buildings still stand in downtown alone, and the Coliseum will certainly feature again during the 2028 Olympics.

London-born architect Robert Stacy-Judd moved to Los Angeles in 1922. His most famous commission was not a residence but a commercial building—the Aztec Hotel, built in the city of Monrovia on a stretch of road that was once the famous Route 66. Designed in a Mayan Revival style, the 1925 hotel was built in the context of a generalized taste for architectural exoticism that flourished in Southern California at this time. The mid-to-late 1920s were the heyday of interest in Meso-American archeology and the idea that Native American styles could be the basis for a new all-American architecture. Proponents of the Meso-American (or pre-Columbian) style viewed it as a welcome return to the folk-like and primitive, and Stacy-Judd became a prominent exponent of the Meso-American idiom. A flamboyant publicist and showman as well as an architect, Stacy-Judd wrote and lectured about Mayan architecture and traveled to the Yucatan jungles to explore Mayan pyramids. By 1930, public interest in both Meso-American architecture and Stacy-Judd had waned. But his writings and lectures, and his Aztec Hotel in particular, had captured Dr. Atwater’s fancy, and the dentist commissioned him to build two Hopi-inspired homes perched atop a hill next to Elysian Park. Robert Stacy-Judd’s Atwater Bungalows combine the features of a Pueblo Indian kiva with the fantasy of a Hollywood stage set. The multiple contradictions of Stacy-Judd's cross-cultural transvestism–an Englishman in search of an "All-American" architectural style–reveals much about Pan-Americanism, appropriation, and the diverse contemporary uses of architectural styles lifted from Ancient America. Former architecture critic for the Los Angeles Times Christopher Hawthorne, now L.A.’s design tzar, has written that “To wander through Robert Stacy-Judd’s neo-adobe Atwater Bungalows …is to be convinced that you are, first, completely isolated from city life and, second, that you are in a place that could only be Los Angeles.”

Salkin House (1948) — the “Lost Lautner” of Elysian Heights

Postcard from Elysian Heights

In the opening decades of the 20th century, in the era of silent movies, Edendale was widely known as the home of most major movie studios on the West Coast. The district’s heyday as the center of the motion picture industry was in the 1910s but by the 1920s the studios had moved elsewhere, mostly to Hollywood, which would come to supplant Edendale as the “movie capital of the world.” In the years prior to World War II, Edendale had a large artist community and a large communist community. Many of its residents were transplants from the Eastern United States or the Soviet Union. When the Edendale red car line ceased operations in 1940 and the Glendale Freeway was built, the neighborhood was essentially split into two distinct sections overnight. What to call this new neighborhood south of the 2? Well, because of the neighboring park below it, Elysian Heights seemed to make the most sense. Elysian Heights as we know it today began to develop in the early 1900s when the Semi-Tropic Spiritualist’s Association laid out their first tract in 1905. They left portions of land intentionally empty as a public space to hold their revivals and seances and drinking parties. The Spiritualists who lived on the hills surrounding the campground would come down and gather in the field to drink and dance the night away. Since the 1910s, Elysian Heights, along with what was once known as Edendale, have been home to many counter-culture, political radicals, artists, writers, architects and filmmakers in Los Angeles. Elysian Heights is also known for architecturally notable and historic homes such as the Paul Landacre House, the Klock House, the Judd-Atwater bungalows, the Ross House (Al Nozaki, the famed art director who designed the martian war machines in George Pal’s 1953 sci-fi classic “The War of the Worlds”, lived there during the 1950’s and 1960’s), and Rudolph Schindler’s Southall House. It is also home to Salkin House (1948), the “Lost Lautner” on Avon Terrace, pictured. Elysium in Greek means Paradise.

The legend of El Camino Real and its bells

Along Highway 101 between Los Angeles and the Bay Area, cast metal bells spaced one or two miles apart mark what is supposedly a historic route through California: El Camino Real. Variously translated as "the royal road," or, more freely, "the king's highway," El Camino Real was indeed among the state's first long-distance, paved highways. But the road's claim to a more ancient distinction is less certain. In fact, the message implied by the presence of the mission bells – that motorists' tires trace the same path as the missionaries' sandals – is largely a myth imagined by regional boosters and early automotive tourists. According to Nathan Masters, host and executive producer of Lost L.A., regional boosters saw California's missions – many of them long-neglected and crumbling into ruin – as a place where tourists could commune with California's romantic past from the comfort of their modern machines. To clothe El Camino Real with mythic significance, they invented sentimental stories about Franciscan fathers traveling along the road from mission to mission, which were supposedly spaced one day apart along the trail. "El Camino Real was a product of the same impulse that gave us the Spanish Colonial Revival in architecture – imparting an exotic hue to the region as a way to attract more tourists and settlers,” explains Matthew Roth of the Automobile Club of Southern California Archives. Between 1906 and 1914, 400 roadside markers were placed along an approximation of the original footpath.

If you ever find yourself on Cahuenga Boulevard, you can see one of these bells at the entrance of El Paseo de Cahuenga Park, which is situated by a bus stop just after Starbucks. On the other side of Highway 101, Hogwarts Castle, a small-scale simulacrum of an actual castle, sits dormant while Universal Studios Hollywood remains closed. The Wizarding World of Harry Potter theme park is itself a copy of a copy. It pretends to copy the books when in reality, it is merely copying the sets and props from the films that unfaithfully copied the books in the first place; things are rarely as they seem in the land of immersive make-believe. Los Angeles, the spiritual home of fairytales, is full of castles; or at least movie-set-formed notions of how a castle ought to look. It’s a city that has been (re)inventing itself from the beginning: palm trees were imported to match the fantasy image that was being sold to lure people in. Unbeknownst to most, the state of California was named after Calafia, a fictional queen who ruled over a mythic all-female island thought to be a terrestrial paradise like the Garden of Eden or Atlantis. In 1530, when Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés arrived on what is now known as Baja California, separated from the rest of Mexico by the Sea of Cortez, he named the land “California”, after the name of Calafia’s island in Las sergas de Esplandián (The Adventures of Esplandián), a 1510 chivalric novel series written by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. Once the name started being used on maps, it stuck.

Postcard from Rustic Canyon

Some say L.A. has no history. Yet the past is all around us in the (fading) grandeur of the city’s buildings, elegies of an earlier time. In 1913, an influential band of revelers known as the Uplifters Club bought part of Rustic Canyon in Pacific Palisades, christened it Uplifters Ranch and built secluded getaways around an elaborate clubhouse. The ranch is a lush, almost rural, residential sanctuary washed by spring fogs and cool ocean breezes. While the exclusive men’s club was dissolved long ago, its legacy is a dreamscape, an odd assortment of three dozen fanciful cottages and lodges tucked in a remote canyon near Will Rogers State Historic Park. Like sentinels of an earlier age, they are whimsical and mysterious. A few have huge ballrooms. Some are log cabins hauled in from the set of an early silent film. Others sport fanciful card parlors and Prohibition-era “basement bars.” Serene, almost magical, the ranch is said to be the last place in town where one can find a creek that hasn’t been filled, lined with concrete or funneled into drainage pipes. The ranch was meant to be a kind of utopia. Latimer and Haldeman roads--the principal streets--are narrow, shady lanes with no curbs and only a few street lights, much as they were during the Uplifter era.

Nearby, a World War II-era enigma serves as a fascinating historical ruin in a metropolis quick to demolish its past.

Steeped in folklore, the fabled Murphy Ranch was supposedly a pro-Hitler American fascist compound constructed by Nazi sympathizers during the 1930s. Wedged between Will Rogers and Topanga Canyon State Parks, this secluded 55-acre stretch of Rustic Canyon in the Santa Monica Mountains was bought by the heiress Winona Stephens and her husband, Norman, while under the influence of a charismatic German—Herr Schmidt. He claimed a psychic vision told him America would lose the war and that once the dust settled over the ruins of Los Angeles he and his band of sympathizers would emerge from Rustic Canyon to help usher in the new fascist state in America. Murphy Ranch was intended to be a self-sufficient community—but that didn't mean sacrificing comforts and luxuries. By 1941 there were plans to build a four-story, 22-bedroom mansion with multiple dining rooms and libraries. Whatever the motives or apocalyptic expectations of the group, the fancy mansion never materialized. In December 1941, right after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI raided Murphy Ranch and took Herr Schmidt into custody. Norman and Winona sold the compound in 1948. Today, much of the Ranch has been demolished or covered in graffiti, but several structures still remain, including a 529-step concrete staircase down to the encampment. Eerily quiet, what’s left of the abandoned Nazi ruin lies hidden among the groves of ancient oaks, ponderosa pine and eucalyptus, a reminder of the futility of human endeavors. Mother Nature has definitely won the battle.

Tales of the L.A. River

The Los Angeles River was paved over in 1938 after a series of devastating floods. The flooding forever altered Southern California's relationship with the elements. Intense rainfall and flash flooding were as much a part of the region's natural cycle as hot summers and Santa Ana winds. But this was the first major flood to occur since the population boom of the 1920s and '30s put neighborhoods in the path that storm runoff had followed for eons. The concrete water sluice, barely a trickle in spots for most of the year, has been used as a backdrop in countless pop videos and movies, including Terminator 2 and Drive. Because of its stark urban wasteland appearance and flat riverbed, it has always been an ideal location for shooting. The bridges overarching the riverbed are architectural treasures designed in the art deco style, each a little different from the next. Thanks to Friends of the L.A. River, the manmade channel has begun to take on features of a natural river in certain sections. Rushes and reeds have flourished, as has the bird population: herons, egrets and ducks now occupy the small islands in the stream. Water has always played a starring role in the story of Los Angeles; now it is possible to connect to the city’s riparian past by walking or cycling along the banks of the much reviled “concrete coffin.”

The vision is for continuous and uninterrupted movement along the L.A. River which would connect neighborhoods to the River, and create an interconnected network of parks and greenway from the mountains to the sea. At least that was the plan back in 2013, when completing a continuous 51-mile greenway and bike path along the river by 2020 seemed both possible and far away. Today, it is more of a patchwork quilt, very much in development, with pocket parks springing up as well as the rather impressive North Atwater pedestrian bridge, built for equestrians and pedestrians alike, which was supposed to cost $6 million but ended up costing $16 million. With a bit of a sailboat-like design, it is undoubtedly an elegant piece of engineering, but a stark contrast to the makeshift shelters of the homeless people living along the L.A. River’s concrete banks. There is still a sense of this being an overlooked place, which is part of its charm, but it also means being confronted by some of the hardships people face. That might deter some visitors. To me, the river is a beautiful example of the resilience and regenerative power of nature. The region’s birthplace, once a thriving, unifying water source for the Tongva peoples and wildlife, is alive again. It is also an example of human grit. In 1986, writer Lewis MacAdams declared the River open to the people and swore to serve as its voice. And so, Friends of the Los Angeles River (FoLAR) and the River Movement were born. Sadly, MacAdams died on April 21, 2020. Andy Lipkis, executive director of the environmental non-profit TreePeople, said MacAdams has inspired him and others who pioneered L.A.’s early environmental movement.

But bringing back the L.A. River is also a way to combat L.A.'s culture of forgetting and erasing its history. As nature writer Jenny Price put it: "What makes the L.A. River so peerlessly amazing is that its city actively "disappeared" it: We stopped calling the river a river. And it all but vanished from our collective memory. ... This act is unparalleled: A major American city redefined its river as infrastructure; decreed that the sole purpose of a river is to control its own floods; and said its river now belongs in the same category as the electrical grid and the freeway system and will forthwith be removed from the company of the Columbia, the Allegheny, the Salmon. In a city with a notorious, extreme tendency to erase both nature and history, L.A.'s ultimate act of erasure has been not just to forget but to deny that the river it was founded on runs 51 miles — 51 miles! — right through its heart."

Remembrance of things past

Twin Peaks was destination television in 1990 and ‘91. The premiere of Twin Peaks on 8 April 1990 was a seismic event in popular culture. It was a fleeting moment when art infiltrated the mainstream, although Twin Peaks did not start as the cult phenomenon it would become later. Today, different Americans are living in different versions of the same country, and social media makes people double down on their attitudes. But back then, there was a shared experience. That’s where the term “water cooler moment” came from. No such common baseline exists today. Twin Peaks has always been, at its core, an exploration of the duality of good and evil, past and present. The original series embraced nostalgia by contrasting the town’s sinister underbelly with the quaint echoes of the 1950s on its surface, from the retro Double R diner’s cherry pie to the Miss Twin Peaks beauty pageant. The murder of the high school homecoming queen strips the veneer of respectable gentility from the picturesque rural community to expose the seething undercurrents of illicit passion, greed, jealously and intrigue. Twin Peaks, like Lynch's Blue Velvet, is deliberately set in what looks like the "perfect" country town. Everyone is white, the local lawmen are honest and upright males, the economy relies on the local logging industry and everyone knows everyone else. It's a wholesome, stylized version of the past, an artifact from the 1950s. He did this deliberately in order to highlight the debauchery that existed beneath the surface. Lynch has always been fascinated with wholesome ideals and the decidedly unwholesome truths that prop them up. So while Twin Peaks looks like the perfect town, its residents hold dark secrets, sex and crime are just around the corner and a demon-creature is possessing a resident and making them commit murder. “There’s a sort of evil out there,” says Sheriff Truman in an episode of the show. That line gets to the heart of Lynch’s work, which reflects the dark, ominous, often bizarre underbelly of American culture. The nuclear family? At best a cheerful deception, an infinite nightmare at worst. The prom queen is a coke-addicted prostitute and victim of rape; her rapist and eventual murderer is a respectable corporate lawyer, her father. The ghost of Laura Palmer hovers over everything, as does the specter of Bob, the Black Lodge (headquarters of a purgatorial alternative universe), and the omnipresent undertow of “the evil in these woods”. With the breakdown of a shared reality due to a refusal to agree upon facts, and the prospect of parallel or twin realities now upon us, David Lynch's iconic TV series was a chillingly prescient vision of modern America, albeit through a very retro lens.

Postcard from Kansas City

There was a Kansas City, Missouri long before there was a State of Kansas or a Kansas City, Kansas. Situated at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers, early residents of the area found inspiration for the word Kansas from the Kansa Native American tribe. Kansas City, MO produced two uniquely American geniuses/imagineers that forever altered the physical and cultural landscape of the country. One of these men built a magic kingdom, a fantasy world that offered non stop family fun, and a complete escape from reality. The other one moved to Hollywood and opened a theme park. The last one is Walt Disney, of course. The first is J.C. Nichols, the city’s major real estate mogul, who built the stunning Country Club Plaza in 1923, the first planned outdoor shopping mall. Nichols also helped introduce racial segregation to the city’s neighborhoods, having developed about 50 blocks worth of residential homes with covenants that forbade black or Jewish residents from ever buying them.

In 1955, the all-white Kansas City, Missouri school board did not resist the Supreme Court ruling that ordered the desegregation of public schools. But the members did manipulate attendance boundaries to ensure white schools were separated from black schools. Troost Avenue was the most obvious border. It has been Kansas City’s symbolic and literal boundary by explicit design ever since and is widely seen as one of America’s most prominent racial and economic dividing lines. In the early 1920s, Walt Disney, a man with a Brobdingnagian talent for the fantastic and chief architect of enchanted alternate reality, fed a tame mouse he’d named Mortimer at his desk in a red-brick building near Troost. This mouse later became the model for a character known as Mickey Mouse. Disneyland, Walt Disney's metropolis of nostalgia, fantasy and futurism, opened on July 17, 1955.

Missouri is a magnet for stranger-than-fiction true crime stories. The saga of a self-proclaimed priest who spent several years in Missouri is the subject of a fascinating new podcast, Smokescreen: Fake Priest. Father Ryan, who also goes by Ryan St. Anne Gevelinger, Ryan St. Anne Scott, Ryan Patrick Scott, Father Ryan St. Anne and Randell Stocks, was accused of stealing from his followers — mostly older women, widows and aspiring nuns who yearned for a traditional Catholicism. The fake priest came to Armstrong, Missouri in April 2014, presenting himself as a Benedictine abbot — black robes, clerical collar and all. The podcast provides a worthwhile glimpse into the life of a grifter, and the consequences of unquestioned faith despite rampant warnings about danger. Meanwhile, Richard Scott Smith is the subject of Love Fraud, who over the past 20 years used the internet and his dubious charms to prey upon unsuspecting women around Kansas City, Missouri in search of love — conning them out of their money and dignity. The series is a fascinating journey, mostly because of the women’s collective effort to catch him. But it also serves as a cautionary tale of how apparently intelligent, sensible people can be susceptible to the snake oil being peddled by a clever salesman.

No One Saw a Thing tells the story of Ken Rex McElroy who terrorized the town of Skidmore, Missouri for decades. On July 10, 1981, 60 townspeople surrounded his truck and shot him dead. The shocking circumstances of his murder garnered international attention. However to this day, no one's claimed to have seen a thing. This gripping true crime mini-series examines the unsolved and mysterious death of McElroy, now considered one of the most infamous acts of vigilantism in American history, and explores the corrosive ripple effects of violence in small-town America. As if things couldn't get any more strange, Kansas City was also home to Tyler Deaton, the Pied-Piper-like leader of a radical Christian cult known as IHOP (International House of Prayer). It was claimed in December 2012 that Tyler Deaton was involved in sexual affairs with at least three other men who lived at the religious community he led. The charismatic Christian’s wife, Bethany Deaton, was killed for fear that she would tell her therapist about being sexually assaulted. Somehow it makes total sense that hiding 150 feet below the city is Subtropolis, a 55 million square foot storage cave that hosts a wide array of businesses seeking to cut costs and utilize the underground for efficiency. Here, you will find one of the most protected data centers in the world where all our internet information lives. You might say it's a city that is literally built on secrets. And make-believe.

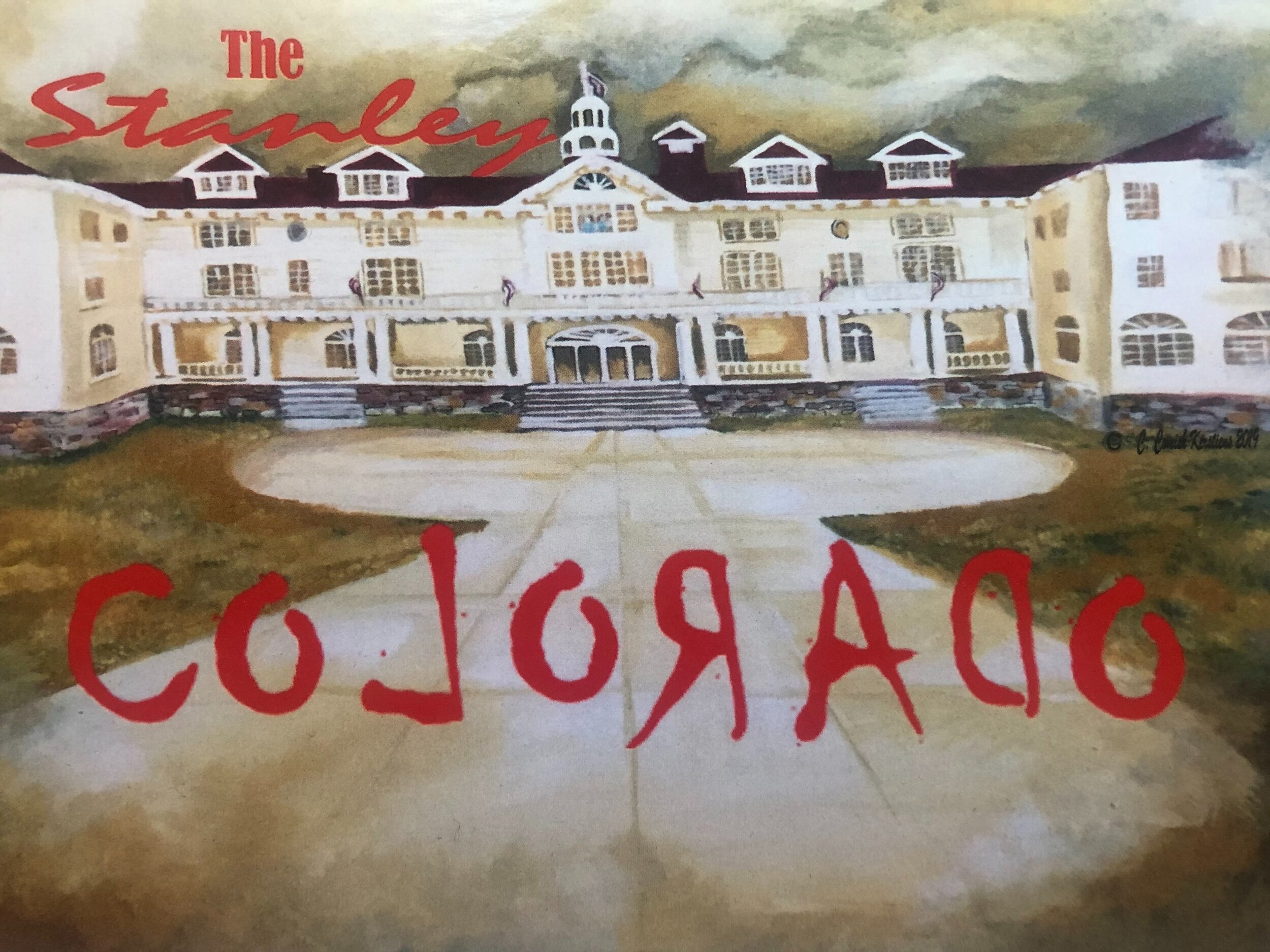

Postcard from the Stanley Hotel

Nestled at the eastern entrance of Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP), just 90 minutes from Denver, Estes Park is known as "Colorado's original playground." The town is celebrated for its stunning mountain landscapes, free-roaming wildlife, and endless opportunities for outdoor adventures. A standout feature is the Trail Ridge Road, one of Colorado's most famous scenic routes. This paved highway, the highest continuous one in North America, reaches an altitude of over 12,000 feet and offers breathtaking views from Estes Park to Grand Lake, making it a must-visit for travelers.

Yet, Estes Park's allure goes beyond its natural beauty. It’s also home to the historic Stanley Hotel, a grand and isolated resort that inspired one of the most iconic horror stories of all time—Stephen King's The Shining. After spending just one night at the hotel in the 1970s, King was inspired to write his 1977 novel, which later became a classic horror film.

The Stanley Hotel, built in 1909 by Massachusetts couple F.O. and Flora Stanley, has since earned a reputation as one of the most haunted hotels in the U.S. Guests and staff alike have reported eerie occurrences. Mrs. Stanley's Steinway piano is said to mysteriously play by itself in the music room at night, while Mr. Stanley allegedly appears in photographs. Unexplained events such as lights turning on and off, bags being unpacked, and ghostly laughter of children echoing in the hallways have all been reported, cementing the Stanley’s place among the nation’s most active paranormal sites.

For fans of King’s chilling novel and film adaptation, a visit to the Stanley Hotel provides a unique glimpse into the eerie inspiration behind The Shining.

Postcard from Utah

The dusty and dramatic eastern Utah landscapes around Moab used to portray HBOʼs futuristic theme park in Westworld have appeared on both the big and small screen dozens of times before. The desert scenes in Thelma & Louise, while pretending to be the rather flat ‘New Mexico’, are the spectacular sandstone landscapes of the La Sal Mountains, Route 46, southeast of Moab in eastern Utah; Arches National Park, to the north of Moab and Canyonlands National Park to the southwest. The spectacular gorge of the final scene is not the ‘Grand Canyon’, but the Colorado River flowing through Dead Horse Point State Park, about 30 miles southwest of Moab. The police chase is at Cisco, Utah. Filming also took place at Thompson Springs and Valley City where you can stay at Desert Moon Hotel which has been serving the greater Moab area since the Uranium Boom days of the early 1950's.

There’s rugged beauty at every turn when you drive Highway 12, constructed in 1914, passing through some of the nation’s most rugged and diverse landscapes. Spanning 124 miles, SR-12 plays host to two national parks, three state parks, a national monument, and a national forest. From one of the world’s highest alpine forests to the rust-tinged walls of Red Canyon, expect to see golden-colored aspen leaves accent against the evergreens in fall while the colorful rocky scenery changes from pink to beige to yellow depending on which geological time period you are traveling through. You'll also come across the Dixie National Forest, called so because of the heat and all the southerners that settled there to grow cotton for the Mormon church. Utah is home to more than 2 million Mormons. Mormon settlers began a westward exodus in the 1830s. When they arrived in the valley of the Great Salt Lake, outside the boundaries of the United States, in 1847, they felt they had found a home.

Utah's spellbinding red-rock desert and high-altitude forests are just a few of the wonders to discover in heavenly Zion National Park. Mormon explorers arriving in this red-rock wonderland in the 1860s were so overwhelmed by the natural beauty of Zion Canyon and its surroundings that they named it after the Old Testament name for the city of Jerusalem. For Mormon pioneers, Zion was often used to mean the Kingdom of Heaven, sanctuary or a happy, peaceful place. If you’ve ever been to Zion National Park, you can understand why they felt this way about this sacred place.

Postcard from Ohio

It’s hard to predict what the summer of 2020 will be remembered for. The coronavirus pandemic has brought tectonic change to almost every part of life, but with no specific triggering event to rally around, all we have are ripples: cancelled plans, the claustrophobia that comes from pandemic fatigue, and the exhaustion that comes from a torrent of calamitous events in the news cycle. There was one blessing for me, though. Unable to travel, I had nowhere to go but my backyard. I got to sit and savor the beauty of my little patch of heaven--in my whole adult life, I’ve never had a garden to plant things in. Working from home, I got to see and actually interact with my neighbors. I learned to love Columbus, and the people in it. Other dramatic crises—wildfires, floods, civil uprisings, the ever-looming election—added to the uniquely exhausting power of the pandemic. But I’ll always remember sitting on my back porch with Jackson by my side, listening to the reassuring sound of hourly-striking church bells, a vestige of regularity from another time in an upended world.

The truth is out there

The X-Files debuted in September of 1993, the same year Bill Clinton took office. Most female law enforcement characters today have been informed by Gillian Anderson’s shoulder-padded, eye-rolling, Scully. An iconic pop-culture phenomenon in the 90s, The X-Files was a landmark in feminist screenwriting and groundbreaking in its presentation of a truly equal TV partnership. Dana Scully was the skeptical rule-follower led by logic. She was brilliant and capable with her feet firmly on the ground, diametrically opposed to her partner Fox “Spooky” Mulder’s head-in-the-clouds, follow-the-spaceship approach. Critics have decoded The X-Files in manifold ways, including as an allegory of illegal immigration. Indeed, it hardly seems coincidental that the show’s climb to cult status took place during a period marked by nationalist discourse obsessed with borders, so-called “illegal aliens” and immigration. The topicality of both The X-Files and paranoia about an “alien nation” were symptomatic of the political moment. The X-Files was popular in the 90s because it expressed the high degrees of complexity emerging with the post-industrial era. Its characters were alien and alienated. The visual aesthetic became, in turn, a touchstone for the distrust, tension and angst of the nineties. The X-Files premiered right around the time that the internet was becoming readily accessible. Because of this, it has a naively optimistic charm, a relic from a (relatively) innocent pre-9/11 era when America hadn't been so deeply threatened and could turn inward. It's about belief and faith in something that exists on a higher plane. But it also represents a full-blown default mistrust in the world as it was presented to us, an effective primer on recent trends in online misinformation. The show's infamous tagline, "THE TRUTH IS OUT THERE," may look a tad anachronistic in a post-truth world marred by internet-fueled conspiracy theories. Nostalgia-driven tv shows like The X-Files, firmly embedded in the cultural milieu of the 90s, serve as the ultimate emotional pacifier, an antidote to the increasingly unpredictable nature of daily life in the shadow of Covid-19.

Flag wars

Imagine a utopia. Queer paradise. A place where you are constantly surrounded by pleasant, like-minded people that all get along. A place where you never have to worry about discrimination or prejudice. Life is just easy-going without any unnecessary negative experiences. Theoretically that’s what a gayborhood, or a neighborhood with a large number of LGBTQ+ residents, is supposed to be. And while there are plenty of benefits to living in a place filled with people like you, there also comes some strong negative impacts.

Linda Goode Bryant and Laura Poitras’ 2003 documentary Flag Wars follows the conflict in a Columbus, Ohio neighborhood between the gay and African American communities as gay white homebuyers begin moving in and gentrifying the neighborhood. Filmed in Columbus’s Olde Towne East neighborhood over a period of four years, it looks at the casual way in which the displacement of the African American community occurs.

To give some historical context, Olde Towne East was once the crown jewel of Columbus. Back in the last half of the 19th century, the city’s most intelligent, creative, wealthy and powerful citizens all resided in this neighborhood. The so-called “white flight” began with the introduction of the freeway system in the 1950s, more suburbs, and desegregation. By the 1970s, the neighborhood had become a predominately African American community. The once grand and opulent mansions were either gutted of their expensive amenities (such as copper plumbing and porcelain sinks and bathtubs) or partitioned and converted into apartments and nursing homes.

LGBTQ folk began moving into the area in the 1990s—attracted by and renovating its relatively inexpensive Victorian homes—increasing property values and displacing the neighborhood’s working-class families, many of them African American. By the mid 90s people had stopped dying of AIDS thanks to major advancements in antiretroviral treatments. The AIDS epidemic had a devastating effect on the gay community. This period marks a moment in gay history when LGBTQ folk could once again allow themselves to look to the future with hope, a joyful new dawn after a decade of death and shame.

While shared experiences of oppression could have laid a foundation for solidarity between the two groups, that possibility wasn't realized. Instead, many of the new residents called on police to crack down on the slightest violations of city code committed by black residents. Throughout the film, newcomers use civil law to speed up the process of removing the African American community. This includes having parts of the neighborhood declared historic to create restricted housing codes, fighting the presence of low-income housing, and making code enforcement complaints. One such newly introduced regulation stipulates that longtime resident, Jim, must remove an African-style sign from above his front door while his newer neighbors are permitted to fly rainbow flags from their properties, hence the film’s title.

Extreme nonchalance best describes the prevailing attitude of the white newcomers towards the black community, which at times is hard to watch. At one point in the documentary, while attending a neighborhood meeting a member of the queer community states, “If you don’t want to renovate it, then don’t live in it.” Jim explains that most of these people do not have the money to allocate funds to the upkeep of their homes.

As the new residents restore the beautiful but run-down homes, black homeowners fight to hold onto their community and heritage. The inevitable clashes expose prejudice and self-interest on both sides, as well as the common dream to have a home to call your own. Winner of the Jury Award at the South by Southwest Film Festival, Flag Wars is a candid, unvarnished portrait of privilege, poverty and local politics taking place across America. While twenty years have passed since the film was originally shot, it could not be more relevant today.

Back to the land: the enduring dream of self-sufficiency

I started observing and documenting American utopian movements several years ago, having always been drawn to the idea of pastoral simplicity myself. On further investigation, it became clear that the desire to carve out a space in the wilderness is the essence of the American dream, dating right back to when Europeans first “discovered” America in the 15th and 16th centuries; communes have popped up all over the continent ever since, often intertwined with spiritual movements.

By the mid-70s, the commune period had ended but the back-to-the-land movement was still in full swing: radical social experiments in group living had been replaced by individual families’ radical experiments in self-sufficiency. In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, reducing waste has resurfaced as a priority, with a renewed appreciation for sustainable living. Could this mark the beginning of a new evolutionary stage for communal living?

Homesteading taps into an ever-present American urge to reinvent ourselves in the semi-rural wilderness. In the 1970s, another "white flight" exodus consisted of white, well-educated college kids from middle-class or wealthy backgrounds going back to the land. For many, the choice to live a life of radical austerity and anachronism was certainly a rebellion against the comfort and prosperity of their Eisenhower-era childhoods, but that same background of comfort also offered a security and safety net that made such radical choices possible.

For some, trust funds and allowances actually financed their rural experiments; for most others, family support was more implied than actual—if things really went wrong on the farm, they knew, their parents could bail them out or take them in. But even those who had cut ties with their families altogether were still the recipients of a particular, inherited confidence.

Today, we are seeing another radical shift as working from home means that a rural life of self-sufficiency is possible, thanks to wi-fi. We are already seeing well-heeled residents leaving New York City in favor of the Hudson Valley and further afield. If the new normal is the distributed company, how will that impact cities? The rapid adoption of remote work and automation could accelerate inequalities if white collar professionals spark a mass urban exodus.

In the shadow of the Vietnam War and amidst widespread social upheaval, the 1970s remains the only time in the nation's history when more people moved to rural areas than into the cities. As author Kate Daloz maintains, “The sudden, spontaneous back-to-the-land movement emerged from the collision between this crushing, apocalyptic fear and the generational confidence that convinced its young people they were still entitled to the world as they wanted it.”

At no other moment in American history had anyone seen anything like the shift that happened as the 1960s turned into the 1970s. To a privileged generation exhausted by shouting NO to every aspect of the American society they were raised to inherit, rural life represented a way to say yes. Similarly, when this pandemic is over, our lives may never exist in the same way again.

The Marietta Earthworks

I first became fascinated with Indian burial grounds after watching The Shining. Although Stephen King’s original novel barely mentions an Indian burial ground or any Native American influence, Kubrick’s film clearly uses the desecration of sacred land as a metaphor for the past’s relentless intrusion on the present. The film also comments on America’s tendency to “overlook” its history of indigenous genocide. The Overlook Hotel—with its ominous maze and the eerie July 4th Ball scene—stands as a symbol of this historical amnesia.

For much of the American public in the 1970s, the idea that Native American history had been trampled underfoot was both new and unsettling. What could be more chilling than the notion that our worst historical mistakes might one day come back to haunt us?

One striking example of this layered past is the Marietta Earthworks site—a 2,000‑year‑old ceremonial center of the Hopewell culture (constructed between 100 BC and AD 500). Located in southern Ohio on the border of West Virginia, this region is considered the epicenter of the Hopewell earthworks. Incidentally, the name “Ohio” comes from the Seneca word ohiːyo’, meaning “good river,” “great river,” or “large creek.”

The modern story of Ohio began in an unexpected place—a Boston tavern in 1786. After the American Revolutionary War had driven the British out, conversations turned to the “wild west” of Ohio and Kentucky. When the Ohio Company landed at the confluence of the Muskingum and Ohio rivers in 1788, they encountered mysterious earthworks and mounds. In fact, early settlers are even thought to have planned their new community around these ancient structures rather than over them. Notably, the British government had already sought to improve relations with the Native Americans in the Ohio territory by restricting settlement there.

However, as colonists pushed westward, conflicts with Native American tribes increased. Stationing troops on the frontier was expensive, so Britain preferred to keep settlers within areas where established military forces could maintain order. If settlers expanded too rapidly, they would bypass British oversight, making it harder to enforce trade regulations like the Navigation Acts—which required goods to move through British-controlled channels. By confining settlements near established trade hubs, Britain could keep commerce under its control.

Beginning with the Proclamation of 1763, the British colonial government had tried to manage westward expansion by restricting settlement beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Intended to reduce conflicts with Native American tribes after the French and Indian War, the proclamation reserved large territories for indigenous peoples. Though it acknowledged their presence, the policy was more about regulating colonial growth for British strategic interests than about affirming Native sovereignty.

These restrictions were among many grievances that fueled colonial unrest and helped spark the American Revolution. Settlers chafed under British policies—including heavy taxation and a lack of representation—which ultimately led to the Treaty of Paris in 1783, formally ending the war and recognizing U.S. independence.

Yet in the years following independence, American expansion continued at the expense of Native American lands. Through a series of treaties, pressures, and forced removals, indigenous communities were gradually displaced. By the mid‑19th century—around 1843—the last significant Native American groups in Ohio had been compelled to relinquish their land.

American independence, while a triumph for the new nation, proved disastrous for Native Americans. Some tribes had allied with the British during the American Revolution and the War of 1812 in hopes of defending their territories, while others chose neutrality. These stances often reinforced the perception of Native peoples as obstacles to progress, rather than as fellow inhabitants of the land. This deep-seated view helped fuel policies aimed at removing Native Americans to open up more territory for settlement and economic development.

As Faulkner famously wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even the past.” The landscapes of Ohio remain steeped in history—a diverse mosaic once home to the Miami, Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandot, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Kickapoo, and many other tribes. Even groups more commonly associated with other regions, such as the Iroquois, Chippewa, and Illini, interacted with Ohio’s indigenous peoples, underscoring the complex tapestry of migration, alliance and conflict in early America.

Note: The inhabitants of the American colonies were known as “Americans” from as early as the 1600s. However, this term originally distinguished British subjects living in the colonies from those in Britain—it was not a national identity in the modern sense.

The Underground Railroad

Established in the early 1800s, the Underground Railroad was a network of secret routes and safe houses for those escaping slavery. The success of the Underground Railroad rested on the cooperation of former runaway slaves, free-born blacks, Native Americans, and white and black abolitionists who helped guide fugitive slaves. The southern Ohio town of Marietta is supposedly one of the Underground Railroad’s outposts, situated where the Ohio and Muskingum Rivers meet.

Evaluating history means dealing with a curious hybrid of exciting untruths/clever humbug. Which is to say, the story of the Underground Railroad is not quite wrong, but simplified; not quite a myth, but mythologized, cloaking white midwestern communities in a gauzy innocence. It took courage almost everywhere in antebellum America to actively oppose slavery, but the idea that Ohio welcomed fugitives with open arms is a fairytale—Ohio was split on the issue of slavery. It was against not only state law, but also federal law to help an escaping slave. Indeed fugitives were only marginally better off in the ostensibly free state of Ohio than across the border in Kentucky. The frontier was not a place of heroism and sweetness and light. It was a place of violence, injustice and devastation for many escapees.

Ohio has a complex historical relationship to slavery and racial capitalism. During the nineteenth century, the economy of Cincinnati—the capital of Southwest Ohio and bordering Kentucky—stood in stark contrast to Northeast Ohio’s. Its wealth was indelibly linked to slavery. Slavecatchers abounded as far north as Dayton, where they made a living catching African Americans seeking freedom and selling them back into bondage across the river. Abolitionists were not welcome in antebellum Cincinnati.

Fugitive slaves were largely on their own until they crossed the Ohio River. And those that did were mostly rescued by free blacks, not benevolent white abolitionists. Most runaways did not head north, and most slaves who sought their liberty did not run away. Only after the Civil War—when it no longer required vision or courage or personal sacrifice—did large numbers of white Americans grow interested in being part of the liberation story. You might call it an early example of retroactive reputation laundering.

That is not to say that there weren’t great men like the famous stationmaster John Rankin in Ripley, Ohio, who used the secret “sign” of a lantern in a window to signal that it was safe to cross the Ohio River to his home. However, this was not a common signal. If it had been, the slave catchers would have quickly learned of it, and used it to identify safe houses.

In the entire history of slavery, the Railroad offers one of the few narratives in which white Americans can plausibly appear as heroes. It is also one of the few slavery narratives that feature black Americans as heroes—which is to say, one of the few that emphasize the courage, intelligence, and humanity of enslaved African Americans rather than their subjugation and misery.

The UR reached its height between 1850 and 1860: slavery lasted for two and half centuries. Estimates are that about 40,000 slaves escaped to freedom on the network, but of them, for every one that made it, between five and 10 were caught, often brutally punished, and returned south to slavery.

Whispers of tunnels, secret rooms and runaway slaves have swirled around the Anchorage, Marietta, Ohio’s mysterious mansion on the hillside built in the 1850’s and completed in 1859, for more than a century. I guess if you look for “evidence” of the Anchorage’s Underground Railroad involvement you will “find” a network of large tunnels in the basement leading into the surrounding hillsides. Geologists, engineers and construction experts believe the tunnels were designed for drainage. I try to be a precise and compassionate observer of America, and this toes the feather line between fantasy and reality.

Inflated tales of emergency hiding places for fugitive slaves may temporarily distract us from tragedy with thrilling adventures, but when the history of slavery gets mixed up with folklore, the severity of the atrocities that took place become minimized. Likewise ghost stories construct a more genteel vision of the past: but they also deflect from the very real pain of racism and the suffering caused by the barbaric institution of chattel slavery. In the words of James Baldwin: “A complex thing can't be made simple. You simply have to try to deal with it in all its complexity and hope to get that complexity across.”

A note on language. By changing from the use of a name—slaves—to an adjective—enslaved—we grant these individuals an identity as people and use a term to describe their position in society rather than reducing them to that position. In a small but important way, we carry them forward as people, not the property that they were in that time. This is not a minor thing, this change of language.

Postcard from Montreal

With its magnetic mix of rugged individualism and European flair, Montreal exudes an irresistible French-Canadian joie de vivre. A short jaunt from most U.S. cities, Montreal feels like a quick trip to Paris. The blend of Canadian and French cultures can be seen throughout the city’s design, art, and food. While the gastronomy scene has always leaned toward high-end French cuisine, a new influx of immigrants is bringing a variety of tastes and textures to the mix. Montreal is also embracing the modern age with the opening of sleek luxury hotels, and avant-garde art exhibits from Quebecois designers and creators.

In an increasingly globalized world, Montreal venerates its deep-seated local culture. French colonists settled Quebec in the early 1600s, and their descendants have never forgotten that intrepid foray, hence the province’s enduring separatist movement and its motto, Je me souviens—“I remember,” rendered pointedly en français, which may or may not be a jab at the British. This city of 1.75 million, set on an island at the confluence of the St. Lawrence and Ottawa rivers, is infused with a pioneer spirit and an unpretentious pride in the homegrown. Here, what to do and where to stay in Montreal now.

Stay:

Discerning travelers will love Hotel William Gray, located in Old Montreal, with elegant rooms that look down on the fairytale rooftops and cobbled streets below. Meanwhile, the grand dame of Montreal’s hotel scene—the Fairmont Queen Elizabeth—reopened in 2017 after a $140 million facelift, with a new look that hearkens back to the middle of last century (think lots of gold and chrome), fitting given its 1958 debut. Make sure you visit the room where John Lennon and Yoko Ono had their 1969 bed-in.

Do:

For a reminder of Expo 67, check out Habitat 67, pictured, one of the first examples in North America of an eco-friendly and affordable apartment building. Designed by Moshe Safdie, the edifice is primarily occupied by renters and owners but it opens up for 90-minute guided tours from May 1 to October 31.

Postcard from Michigan

Back in its heyday, House of David was considered to be “Michigan’s finest summer resort.” The religious colony in Benton Harbor, Michigan consisted of an amusement park, zoo and baseball empire. Members abstained from all vices, celibacy was enforced and profanity was outlawed. Another tenet of their faith was that they must neither shave nor cut their hair. Co-founded by Benjamin and Mary Purnell in 1903, thousands of acolytes flocked to the colony until it all came crashing down in the 1920’s when the group’s leader, Benjamin “King Ben” Purnell, was accused of having sexual relations with minors. The colony split in two and slowly died off over the years. The policy of celibacy among followers resulted in a notable lack of new generations of acolytes to keep the commune going. There are only a few members left now, waiting for the day when Jesus returns and establishes the Garden of Eden on Lake Michigan.

With their utopian goals, messianic movements like House of David are seen by some as models of progressive communitarianism, in ideals if not in execution. But it’s worth remembering that America was shaped by religious renegades seeking a strategic retreat from society. “America began as a fever dream by those who abandoned everything because of their beliefs, dreams and fantasies,” says Kurt Andersen in “Fantasyland.” Every November, we celebrate the seventeenth-century Puritans who arrived at our shore with the desire to build set-apart communities in the American wilderness. The group that set out from Plymouth, in southwestern England, in 1620 included 35 members of a radical Puritan faction known as the English Separatist Church. America represented a fresh page. Throughout American history, religious groups have walled themselves off from the rhythms and mores of society. A hunger for the magic and drama of Holy Roller theatricality combined with the tendency to withdraw into small, private societies is, perhaps, as American as apple pie. And baseball.

Postcard from Roanoke

Tucked into the unspoiled beauty of North Carolina’s Outer Banks, Roanoke Island is steeped in history. In 1587, it became the first English settlement in America. Within three years, the settlers had vanished without a trace. The only thing the Lost Colony left behind was the word “Croatoan” etched into a post. These days it’s a vacation hotspot with paradise beaches and dramatic sand dunes. Sure, most people come here for the beachfront retreats, but I opted for the more tranquil Cypress Moon Inn on the shores of Albemarle Sound. Authenticity is a term that gets bandied around a lot these days, but this place is the real deal, located in one of the few remaining maritime forests in the world. It had an untamed, jungle-like quality which I loved.

Taking a dip from the Inn’s dock, I chose the water noodles over a paddleboard or canoe, which made for a pleasantly refreshing float. Drifting in the cooling water was like taking an aquatic safari through a lush paradise. Floating in between forest, sea and sky, I got a unique glimpse of the spirit and soul of this otherworldly place, with its ancient coastal rhythms. Submerged in the primordial waters, brimming with frogs and dragonflies, I felt connected to a primal energy. My dream state was soon disrupted when I remembered that alligators, water moccasins (cotton mouth snakes) and sharks could be lurking; should I be worried? “I’ve been swimming here all my life, and so far so good,” said North Carolina native Linda, one half of the husband and wife team that runs the Cypress Moon.

The Outer Banks is a 200-mile-long string of barrier islands that support a diverse ecosystem. Visitors are strongly encouraged to admire but not feed the wild horses of Corolla wandering near the beaches of Currituck. The story goes that these magnificent Spanish mustangs are descendants of shipwrecked horses from hundreds of years ago. With Dorian looming, the horses will gather under sturdy oak trees to shelter from the storm. Currituck comes from the Native American word carotank or “land of the wild goose.” The area remains synonymous with waterfowl. Situated on the Atlantic Flyway, Currituck Sound is an ideal stopover for migrating ducks, geese and swans. With sea-level rise and increasingly severe storms, North Carolina’s coastline is under threat. Long may this little slice of heaven remain not only a vacation wonderland, but also a habitat for vulnerable wildlife.

Postcard from Portland

Portland is widely seen as a redoubt of crunchy creatives and nonconformists, the place that the popular comedy Portlandia famously deemed ”the city where young people go to retire.” For some, Old Portland died on January 21, 2011 — the day Portlandia debuted. It tapped into the cultural Obama-era zeitgeist, highlighting contrived lifestyles, emerging technology, DIY mentality, and the organic movement. It poked fun at privileged, white, artsy liberals (“we can pickle that!”) in much the same way Absolutely Fabulous did in 1992 with a pair of selfish, self-indulgent, middle-aged women named Edina and Patsy. Like all of the great shows built on self-mockery, there was a good-spirited intention behind Portlandia that made us care.

But things aren’t quite as ambrosial as they may seem in the Rose City. In recent years, deeply blue Portland has become known for heated clashes between the militant left-wing group antifa and out-of-town, right-wing groups such as the Proud Boys and Patriot Prayer. While Portland itself is politically progressive, Oregon is not, and a white nationalist ideology remains prominent in neighboring Vancouver, WA (or “Vantucky” as it is not so affectionately known), which is just across the bridge. Anti-California sentiment also runs high in Portland. A lot of the time it gets a pass because it's usually leveraged by white liberals against other white liberals. But there is good reason for the resentment. The Portland metro area has been growing by 30 to 40,000 people annually since 2015 and a lot of that is Bay Area refugees. Portland is a dramatic example of a nationwide problem: white “urban pioneers” displacing black communities.

Nature surrounds you in Portland. The Columbia River Gorge, which separates Oregon and the state of Washington, is the crown jewel of the region, filled with tree-topped bluffs and thundering waterfalls including the popular Multnomah Falls. Mount Hood, home to the historic Timberline Lodge which became The Overlook in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, is a 1hr 30 drive through the Douglas fir-filled forest. In another direction, the Oregon Coast is home to the sweeping vistas and misty ferns of Ecola State Park with spectacular views of the iconic Haystack Rock. On North Oregon’s shores, towns like Astoria are the stuff of movie legend. When filming began on The Goonies in 1984, Astoria’s fishing economy was in crisis - and houses were indeed being sold back to the bank. The biggest industry today is tourism but Astoria, while embracing change, is careful not to be hipsterfied. It still has grit. It's a town that welcomes visitors but understands its sole purpose isn't to attract them. "We like to say, ‘Astoria for Astorians,’" said Brett Estes, the city of Astoria's community development director. "Do things that are right for the community, and people will come visit."