I want to name a specific era in gay male life — one that now feels complete.

In the decades straddling the turn of the millennium, gay men moved through a strange second act: after the shadow of AIDS, yet before the digital world unraveled the physical. It was a fragile, luminous window—men who had once been pariahs, many arriving in places like Palm Springs half-expecting death, discovered instead the strange gift of living. Medicines arrived, mortality receded, and desire returned.

What followed was no abstract liberation, but life lived in analog: resorts, clubs, pools. Gayness was spatial. You went somewhere to be among your own. Sleaze wasn’t a failure of taste; it was part of the contract. Clothing-optional resorts, mid-range motels, rules understood without being written down. These places didn’t pretend to be everything. They knew who they were for.

I came to Palm Springs late — late enough to sense the afterglow, early enough to catch the echoes. My first visits were in 2011 and 2013, for Hot ’n’ Dry, a now-defunct conference that began in 2009 and ran annually for sober gay men. Slightly over-choreographed, unmistakably of its moment, it offered a weekend where being gay could still be fun without the booze, bound together by a sense of brotherhood.

Hot ’n’ Dry quietly disbanded in 2015. By the mid-2010s, gay men’s social habits were shifting. Apps like Grindr and Scruff had transformed the way men connected, and the demand for organized events waned. Clothing-optional resorts were also becoming relics of an era that was fading fast.

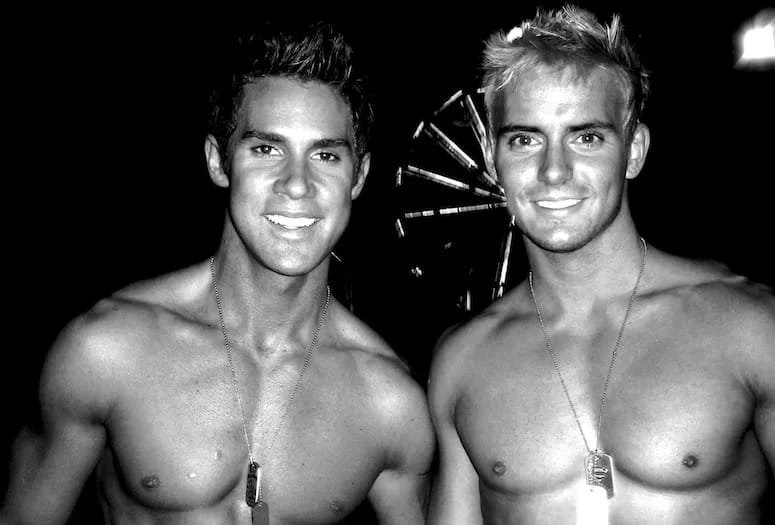

Recently, I checked into what is now the sleek wellness hotel Terra. Curious about its past, I asked what the property had been — and that’s when I fell down the rabbit hole of its history. The doors of the Bearfoot Inn first opened at Christmas 2012, the culmination of more than a decade-long dream by Glen Boomhour and Jerry Pergolesi. It was a men’s clothing-optional motel, designed for a clientele who regarded sleaze not as a flaw, but as part of the appeal.

Reading the reviews over time, you can feel the shift. Early complaints are minor, almost affectionate. Later ones curdle. Guests arrive expecting boutique hospitality, Airbnb polish, professionalized service — and encounter a place that seems baffled by those demands. By 2017, the tone turns bitter on both sides. By 2020, openly hostile. By 2022, it’s gone.

This wasn’t just about management or money. It was about a deeper mismatch: the collapse of a shared understanding of what these spaces were for.

Apps changed that forever. Grindr didn’t create new desires; it rewired old ones. Presence was replaced by availability. Instead of spending an entire day doing nothing by a pool, men were suddenly tethered to a marketplace in their pockets. Social spaces stopped being destinations and became nodes. Once that happened, the chemistry of places like Bearfoot became unstable.

Meth accelerated the collapse.

For many men—especially older ones—it erased fear, suspended time, restored libido, and dissolved the lingering trauma of the AIDS years that had never fully been processed. In contained, sexualized environments, it tipped permissiveness into chaos. Grindr then amplified that chaos, turning what had once been episodic into something ambient and relentless.

Meanwhile, Palm Springs itself was being “fixed.” The Ace opened in 2009 — Hoxton-in-the-desert — ushering in a new clientele of skinny people in black clothes, festival bands, and lifestyle branding. Mid-range sleaze was squeezed out from both sides: too sexual to be respectable, not profitable enough to be luxury. Airbnb rewired expectations without lowering prices or increasing tolerance. Sexualized male spaces came to be framed as exclusionary, problematic, or simply subpar.

COVID finished off what was already dying. Too much hassle. Too little margin. No cultural goodwill left to defend imperfection.

Looking back, I realize I only ever saw Palm Springs’ gay heyday obliquely, from the edge. I arrived when it was still standing, but already hollowing out. The parties had become brand experiences. The resorts were aging. The culture that sustained them was dissolving into something broader, cleaner, and far less legible.

Perhaps we don’t need to mourn these places endlessly. They existed for a very specific kind of desire and risk—now at odds with today’s rhetoric of tolerance and “queer” inclusion. Their reason for being may have simply passed.

But something specific was lost. Not just buildings or businesses, but a shared agreement that gay male spaces didn’t need to justify themselves beyond the people they served. They didn’t ask to be liked by everyone. They didn’t apologize for desire.

From the mid-1990s to the mid-2010s, gay men lived through a historically brief second act — post-AIDS, pre-digital dissolution — when sex, space, and community briefly reassembled before being atomized by apps, lifestyle branding, and rising moral scrutiny.

When Glenn opened the Bearfoot Inn in 2012, gay life was still a distinct social world. Apps ended that. COVID closed the door.

The party didn’t exactly end. It just dispersed.

I hope Glenn and Jerry are somewhere nice now, feet up, pool nearby. Cheers, lads.

Terra Palm Springs is very much not a clothing optional establishment, just so we’re clear! It is a delightful 13-room boutique hotel where holistic wellness is at the heart of every experience.