Every place tells stories about itself. Some are whispered. Others are sold.

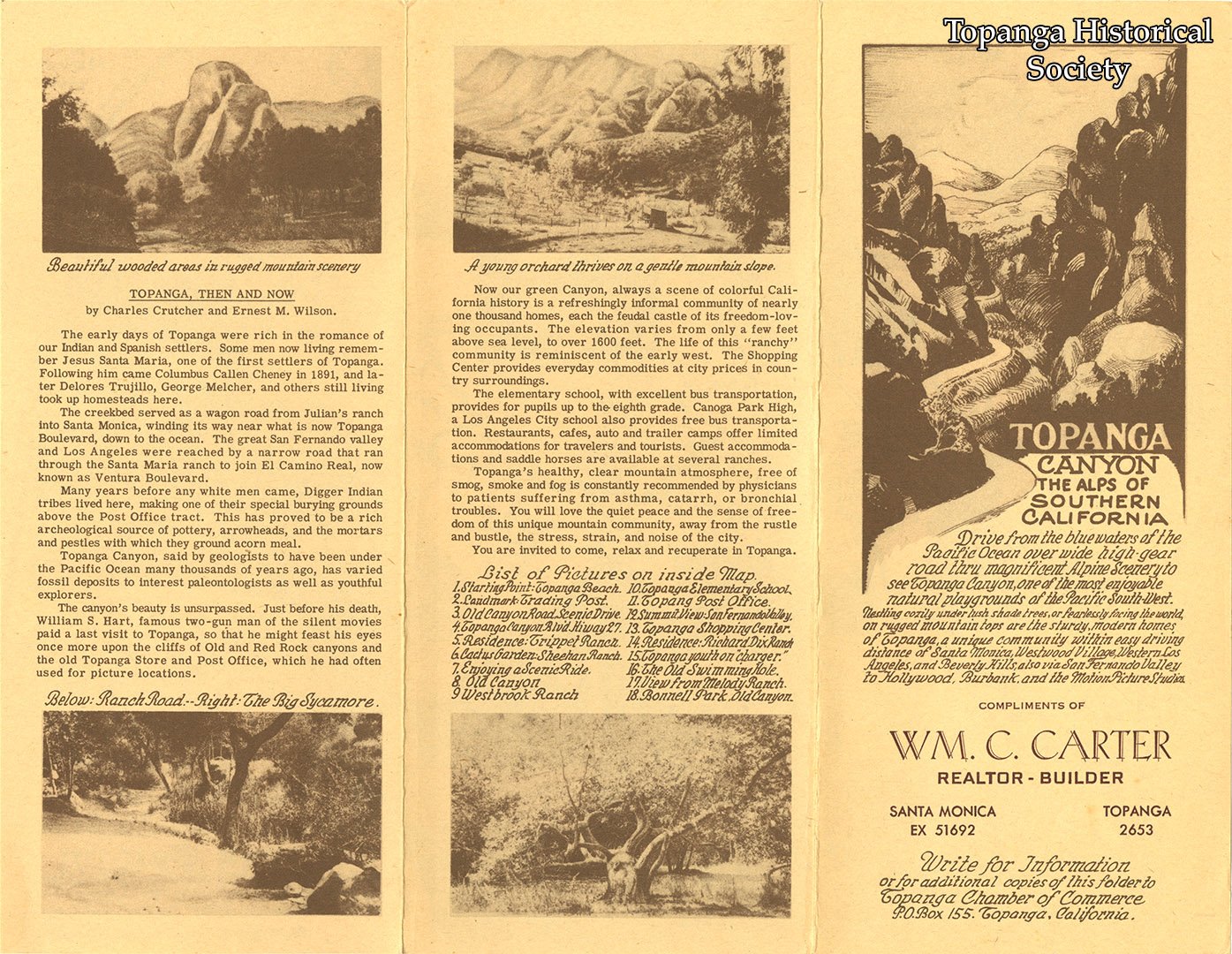

Tucked away in archives and yellowing pamphlets is a body of early 20th-century writing that reveals how Topanga Canyon once wanted to be seen—not just as a place to live, but as an idea. What survives today reads like a blend of travel brochure, civic pride, frontier romance and Hollywood reverie.

One such text opens grandly:

“The early days of Topanga were rich in the romance of our Indian and Spanish settlers…”

From the start, the tone is unmistakable. This is not neutral history; it is booster prose, written to enchant, reassure and elevate. Native life, Spanish settlement, Anglo homesteading, geology, archaeology and movie stardom are woven together into a single, flowing narrative—one that positions Topanga as timeless, storied and quietly exceptional.

The text names early settlers—Jesús Santa Maria, Columbus Calen Cini, Dolores Trujillo, George Melcher—not merely as facts, but as proof of continuity and legitimacy. It situates wagon roads in creek beds, ties the canyon to El Camino Real, and places Topanga neatly between the Pacific and the San Fernando Valley, connected yet removed.

Even the geology is romanticized:

“Topanga Canyon, said by geologists to have been under the Pacific Ocean many thousands of years ago…”

Fossils become not data, but treasure—objects of wonder for “youthful explorers.” Indigenous burial grounds are described with the detached curiosity typical of the era, framed as archaeological richness rather than living heritage. The language is dated, sometimes uncomfortable by modern standards, but historically revealing. It tells us less about ancient Topanga than about how early 20th-century Southern California wanted to imagine itself.

Then comes Hollywood.

Just before his death, the silent-film star William S. Hart is said to have returned to Topanga to feast his eyes once more on its cliffs and red rock canyons. This is not incidental. Hart’s presence functions as a cultural stamp of approval: Topanga is not just scenic—it is cinematic. Worthy of myth.

A second piece of copy, clearly meant for motorists and weekend escapees, shifts the tone from nostalgia to invitation:

“Drive from the blue waters of the Pacific Ocean over wide, high-gear road through magnificent alpine scenery to see Topanga Canyon, one of the most enjoyable natural playgrounds of the Pacific Southwest.”

Here, Topanga is sold as accessibility without compromise. Alpine scenery within reach of Santa Monica. Rugged mountaintops and shade trees. “Sturdy modern homes” that are both fearless and civilized. The canyon becomes a paradox on purpose: wild, but safe; remote, yet close to Beverly Hills, Westwood, Hollywood, Burbank and the motion picture studios.

This is where the famous phrase emerges, sometimes explicitly, sometimes implied:

Topanga Canyon — The Alps of Southern California.

It’s an audacious comparison, and that’s the point. Early Southern California marketing thrived on metaphor. If Europe had mountains, California would have better ones—warmer, closer, freer. Topanga wasn’t just a canyon; it was a lifestyle upgrade before the term existed.

What makes this writing so compelling today is that Topanga never fully abandoned this self-image. Unlike places that urbanized beyond recognition, Topanga absorbed the myth and carried it forward. The ranching era faded. The booster pamphlets disappeared. But the idea remained: a place just outside the city where beauty, individuality and history quietly persist.

These texts are not objective history. They are acts of invention. They show us Topanga not as it was, but as it wanted to be remembered—and perhaps, in subtle ways, as it still is.

In that sense, they aren’t relics at all. They’re mirrors.