There’s a certain type of British pop record — S Club’s “Natural,” Victoria Beckham’s “Not Such an Innocent Girl,” late-period Hear’Say deep cuts — that hits not just the ears but the spine. It triggers pride. Not nostalgia exactly. Recognition.

Because for a brief, incandescent window — roughly 1990 to the early 2000s — Britain didn’t just compete in global pop. We ran it. And we did so with a confidence and lack of shame that America simply didn’t have at the time.

This wasn’t accidental. It was structural.

Let’s get this out of the way: British pop didn’t pretend to be “authentic.” It didn’t hide the scaffolding. It understood pop as design, not confession. Songs were built. Groups were assembled. Personalities were defined. And no one felt the need to apologize.

That alone set Britain apart.

The US still clung to the myth of the lone star: the tortured prodigy, the church-raised vocal miracle, the individual who deserved success. Britain said: here’s the group, here’s the chorus, here’s your Saturday night. And crucially — let’s have some fun. No irony. No apology.

Look back properly at British pop groups of the era and something becomes obvious in hindsight yet invisible at the time because it was treated as normal:

* Mixed race

* Mixed gender

* Different body types

* Different energies

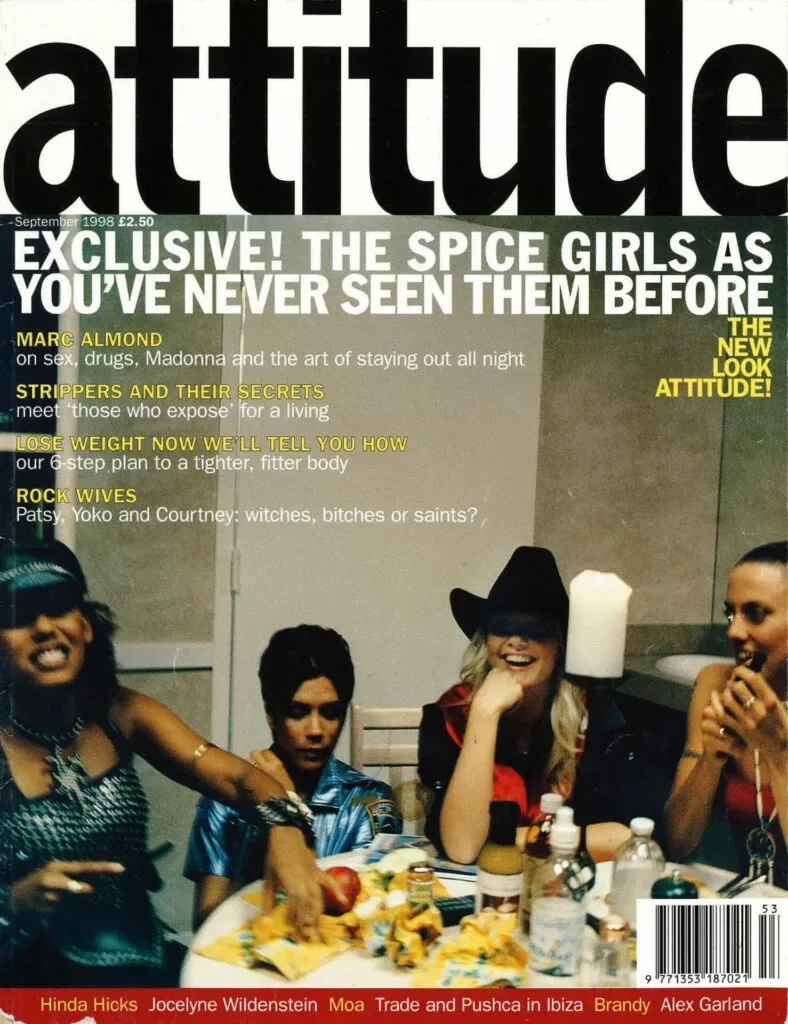

Five. Blue. Eternal. S Club 7. Sugababes. Even the Spice Girls — while all white — carried cultural coding that rejected American homogeneity. Mel B’s Leeds swagger wasn’t softened or exported away. It was the point.

This was radical without rhetoric.

In America, pop groups were still rigidly segregated well into the late ’90s. Black acts were R&B. White acts were pop. Co-ed groups were rare, novelty-coded or short-lived. Diversity was something you marketed as an exception.

Britain didn’t market it. Britain assumed it.

Part of this comes down to Britain’s blunt class awareness. We don’t pretend difference doesn’t exist — we live inside it. That gave British pop an odd realism even at its most artificial.

S Club 7 wasn’t just sunshine and smiles. It was broadcast weekly into living rooms across the world. Not siloed by format radio. Not discovered through subculture.

It normalized a version of Britain that felt modern, plural and forward-facing without turning it into a sermon. I know millennial women from suburban Ohio who were obsessed with S Club. Not despite their Britishness — because of it.

British manufactured pop worked globally because it didn’t try to universalize itself by erasing difference. It exported specificity.

American pop of the era wanted to be aspirationally blank. British pop wanted to be recognizable. You could tell where these people were from. You could hear it. See it. Feel it.

Victoria Beckham’s solo career — often lazily dismissed — is the perfect case study. “Not Such an Innocent Girl” isn’t a flawless record. It’s a little stiff. A little unsure of itself. And that’s exactly why it works.

It’s British pop negotiating American tropes without fully surrendering to them. There’s no illusion of diva transcendence here — just ambition contained by reality. That tension is the sound of Britain at the turn of the millennium.

That ’90s-to-early-2000s British pop window represents something we’ve lost:

* Confidence without cynicism

* Progress without performance

* Craft without apology

We didn’t need to explain ourselves. We didn’t need to signal virtue. We just built pop that looked like the country actually did and sent it everywhere.

We knew it was manufactured. We knew it was commercial.

What made it fun was being slightly behind.

Britain in the late 90s existed in a sweet spot of cultural lag. American pop culture didn’t arrive instantly or intact. It arrived late, filtered and reinterpreted. That delay mattered. It created room to play.

This is where translation comes in.

British pop wasn’t copying American pop in real time. It was translating it, the way a paperback novel changes when it crosses languages. Something is always lost, but something else appears in its place. Tone shifts. Emphasis changes. Awkwardness sneaks in. And sometimes that awkwardness is where the truth lives.

You can see it everywhere once you look.

Billie Piper was clearly being positioned as a British Britney. But she wasn’t Britney Spears. She was a UK teenager trying on American pop fantasy with a faint layer of embarrassment still intact. That self-consciousness made it feel human.

Victoria Beckham reaching for Toni Braxton energy is even more revealing. She never fully surrendered to the role. The voice stayed restrained. The sexuality stayed polite. What you get isn’t imitation, but aspiration constrained by British reserve.

S Club 7 functioned like a British Mouseketeers project, but softened. Less competitive terror, more communal warmth. The same machinery, translated for a country that still believed pop could be a shared experience rather than a blood sport.

Because audiences didn’t yet have total access to the American originals, the British versions didn’t feel inferior. They felt local. The copy wasn’t pretending to replace the source. It was serving a different emotional need.

Back then, you had the US original and the cheaper British version and time between the two. That gap allowed the copy to develop its own identity. And sometimes the knockoff felt more authentic because it wasn’t asking to be worshipped. It was accessible pop.

American pop wanted to be mythic. British pop wanted to be available at Asda.

Cultural lag made that possible. Translation made it interesting.

Now that everything arrives simultaneously, there’s no lag and no mercy. Influence is visible instantly, which means it’s policed instantly. A British Britney would be mocked before the chorus. A local Toni Braxton analogue would be accused of cosplay within hours.

Homogenization didn’t just flatten pop. It killed the joy of approximation.

Back then, being second wasn’t a failure. It was a position. And from that position, British pop built something that felt oddly more honest than the original.

I sometimes think we did America better than Americans.

Not in reality, obviously. But in imagination. In consumption. In tone.

Britain in the 90s felt like an early draft of America. Essentially American, but with worse lighting. Smaller. Less confident. Slightly in awe. And that awe mattered.

Because awe creates care.

We absorbed American culture with reverence, not entitlement. We didn’t assume it belonged to us. We treated it like something powerful and strange arriving from across the water. That distance gave us permission to edit.

As consumers, Britain had a uniquely privileged position. We could take the American original and repackage it without inheriting all the fire and fury that produced it. We got the fantasy without the cost.

We stripped out the parts that felt too heavy. The religious fundamentalism. The guns. The trench warfare of race, region and identity that saturates American life. We could admire the confidence without having to live inside the anxiety that fuels it.

From across the pond, America looked glossy and enormous and thrilling. Like cousins who stayed up too late and spoke too loudly and somehow got away with it. We could dip in, borrow the energy and then step back out again.

That’s what made British pop translation so effective. We weren’t trying to outdo America. We were trying to soften it. To make it livable. To drain just enough intensity that the fantasy could sit comfortably in everyday life.

This is why the British versions sometimes felt more pleasurable than the originals. They didn’t demand belief. They didn’t demand allegiance. They didn’t ask you to buy into a myth of national destiny or personal transcendence.

They just asked you to enjoy yourself.

Growing up in the UK in the 90s meant living with two cultures running side by side. British and American. Local and imported. You could jump tracks depending on the day. Both were available.

Americans don’t get that option. America is not something they get to visit and leave. It’s something they have to survive.

From the outside, America could remain an idea. And ideas are often more fun than realities.

Which is why being American might actually be less fun than consuming America from afar. And why Britain, for a brief moment, managed to turn secondhand culture into something lighter, kinder and strangely more human.